Going to China used to be the “big” vacation trip of the year, not only because it was usually around a 24 hour one-way journey that required at least three flights and a visa but also because it used up just about all of my vacation days for the year. Germany’s vacation policy offers far more than ten vacation days, so this year again I could head back to my birth country without the weight of vacation planning on my mind. With a nonstop flight from Munich to Beijing, the flight logistics also weren’t an issue, so how rough could the experience be?

The trip started straightforwardly enough. I arrived at MUC and was somehow the first economy passenger to board. The A340-600 — the newest A340 in Lufthana’s fleet, incidentally — wasn’t empty for long, though, and we were soon underway. We left the ground into a sea of clouds, but it wasn’t long before we punctured through into abundant sunshine.

Flying northeast with an afternoon departure meant seeing a sunset and a sunrise; I chose a window seat even with just under nine hours airborne, hoping to see at least one of the two. What was more fascinating than the colors of sunset were either the high clouds beneath us or the bypass from the turbofans condensing immediately — normally where it’s difficult to discern airplane movement in flight this time I could see the white trails streaking steadily by. It’s the first time outside of turbulence I’ve had a sense of just how fast planes move, miles above all other forms of traffic. I slept through sunrise.

A few hours after the normal immigration processes, the sun set again, this time illuminating Beijing Airport’s Terminal 3 in a warm, red-orange glow. After a stop in Chengdu, we were on our way to Jiuzhaigou, 九寨沟, a pristine national park pretty much smack-dab in the middle of China.

The area is, with the right timing, spectacularly beautiful. The deep valleys are strewn across the Min Mountains and on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau, so remote from other cities in Sichaun (often anglicized as Szechuan) province that the entire area was nearly inaccessible until the 1980s. To preserve its pristine air and manage the hordes, buses run constantly, picking tourists up and dropping them off at the next stop. As often as the buses come, there is no respect for lines or queueing. Our first day was cloudy, but a brief clearing in the morning showed just how tall some of the mountains nearby were: where I was standing when I took the picture was around 3,000 m above sea level.

The mountains nearby were not the primary focus of the nature reserve, however. The star of the show would be the water: incredibly clear, blue as the sky, ice-cold water that sat in colorful pools that lay at the base of the mountains. The low water level here at Five Colored Pool (五彩池, Wucaichi) was indicative of the low-rainfall season, though this did not stop visitors from streaming onto buses and the boardwalk surrounding the pool.

Earlier that morning, as we rode a bus up to Long Lake (the biggest and highest lake in the reserve) the light and reflections on an incredibly still Rhinoceros Lake (犀牛海, Xiniuhai) were spectacular. This, and the unspeakable pollution due to diesel engines with no aftertreatment, was a distinct downside to the bus system: as the buses stop only in prescribed locations, we were unable to disembark and grab some shots right then. By the time we returned in the afternoon, the perfect reflections were distorted by the now-rippling lake, but the colors of the trees remained nevertheless a nice complement to the blue-green of the water.

In my view, however, the most beautiful parts of Jiuzhaigou were not the random pools or reflections but rather the waterfalls. They weren’t quite as wild or as whimsical as the Fairy Pools, owing largely to endless boardwalks that led up to and then away from each attraction, but on the grandeur scale still mightily impressive.

With good weather, an early start, and malleable feet it’s possible to visit all the attractions in one day. Taking time to explore slowly all the scenery isn’t a particularly bad way to spend two days, either, provided the [frankly outrageous] entrance fees are tolerable. (Per person per day, a bus and entrance ticket is 310 RMB, nearly 50 USD.)

Not far from Jiuzhaigou, and the other half of the name of the Jiuzhai-Huanglong Airport, is Huanglong (黄龙; literally, “yellow dragon”), itself a 5-A rated tourist attraction. Unlike at Jiuzhaigou, there are few waterfalls here. The area has its fame due to multiple colorful pools, shaped over thousands of years. Here also was low season, with multiple signs indicating that what were now dry pools would be overflowing come July rains. The entire route from entrance to the highest pool is walkable on a ten foot wide boardwalk rather than gravel or earth trail, rendering what would otherwise be a Yellowstone-like ruggedness slightly cheesy, as if the area were on display only to attract touristic revenue than promote appreciation of natural beauty. Such finished surfaces are, however, the norm with tourist attractions in China.

The mountains here were still snowcapped, showing just how much of an effect latitude has on snowfall: at 3000 m, the Alps at this time of year would still be positively blanketed. Here there was just a dusting.

Leaving the clean air and clear visibility of Jiuzhaigou, we returned to Chengdu for a day. I had been here before, but nearly two decades ago. In the time since, a museum dedicated to the ruins found at Sanxingdui (三星堆) gained popularity, so foregoing seeing pandas we decided to take a look at ruins unlike others found in China. To this day, it’s still undetermined what civilization this was, where they got their influences, and what happened to the inhabitants. The relics at Sanxingdui are completely unlike artifacts found in sites nearer the Yellow River, long thought to be the birthplace of Chinese civilization.

Chengdu, and specifically its province of Sichuan, is known across China for its theatre. The one-hour performance showcases bits of acrobatics, comedy, drama, and finesse that are sometimes shown in the US during Chinese New Year festivals, but compared to images of bustling Shanghai or the imposing Great Wall are far less recognized outside of China.

The various acts are at first glance disparate but are nevertheless loosely tied together, in total doing a fairly good job of showing a large number of classical Chinese theatric techniques.

The most elusive of these skills to master is arguably bian lian, 变脸, which is the act of changing one’s face using masks or various materials to express different visages. This is the highlight of Sichaun opera and the changes occur very, very quickly. I had seen such performances on TV in the past but seeing it in person was surprisingly impressive.

After the stay in Chengdu, the next stop was Nanjing. We spent a few days visiting family but also had one day in the outskirts of the city, this time with the temperature and humidity cranked on full. The first destination was Niushoushan Cultural Park (牛首山文化旅游区), a massive site of 80 hectares devoted to promoting and preserving Buddhist heritage and culture. Inside the massive Usnisa Palace (which I believe is 世界禅学中心 in Mandarin, or World Zen Center if directly translated — translations between Mandarin and English are still rare for the park) is a show of manifestations of Buddhist practice in life.

At first glance, the intention seems noble, but the price tag suggests something hazier behind the scenes: the estimated price for its construction was a staggering 40 billion RMB, somewhere around 6 billion USD. For a site whose Mandarin name contains “tourist area,” expecting tourism itself to recoup the construction costs — and then to sustain the project — is simply daunting. While the entire site is spectacularly designed, I couldn’t help but feel uneasy at the idea of using a religion to promote tourism that in turn fuels the religion. This seems altogether immoral, though throughout the trip this site was not the only instance I felt this way.

The next day, we visited one of many sites being developed in China intended to bring up the rural, agricultural areas in China, once again promoted through tourism. The government leveled old shacks, built new roads, and added parking lots strategically, all with the intent to prop up rural China through tourist dollars (or Yuan, as it were). The sustainability of such a massive venture is to me questionable and again raises the question of both morality and necessity of government intervention. If the idea fails, the people who will suffer will not be the tourists who simply stop going to such areas but rather the people whose lives are now without their primary means of income. I took no pictures in frustrated “protest” of the concept, but in hindsight it would have been good to document; China’s development almost requires an attentive eye as it seeks to grow and begin wielding its influence.

The end of the trip was Beijing, both our arrival and our departure city. I barely remember the place — I had spent a few days here and there in 1998-2002, either going to the Forbidden City or Great Wall, but never really spending time “in” the city. This time, wanting to revisit civilizations long lost, we headed first to the Forbidden City, where we were instantly greeted with thousands of other visitors with the same idea.

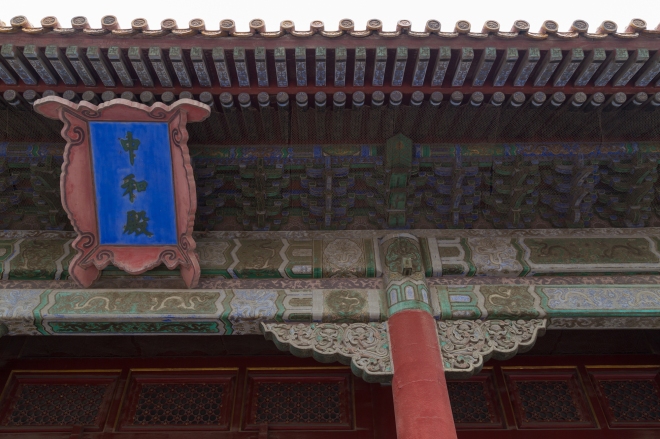

Surprisingly, the air quality was rather excellent while we were there. Apparently the city has a dozen or so pockets of clean air per year, so we were lucky to have visited during such a spell. The other days did no favors for the old temples and buildings of the Forbidden Palace, with some — like Zhonghedian, 中和殿 — in need of a good scrubbing and fresh coat of paint.

For the most part, we also visited in what was not a particularly busy weekend, with many of the side courtyards fairly empty. Even so, beyond the palace walls was a city fully into high-gear I’m sure, even on a weekend.

Leading up the steps to another building, 保和殿 or Baohedian (“Hall of Preserving Harmony”) is the Yunlongshidiao, 云龙石雕, a 250-ton, 50 foot long slab of marble whose intricate design portrays nine dragons and clouds, symbolizing the power that emperors once held.

One of the most [technically] impressive displays in the Palace is the Hall of Clocks and Watches. It’s an indoor showroom suited mostly for those interested in design or function of ancient timepieces ; its niche today in the face of digitalization probably borders on insignificant. One clock in particular stood out to me. Made in London in 1790, on the hour the man inside the clock practices calligraphy, the eight characters taking a minute or two to complete but with painstaking precision.

The Forbidden City is a massive complex, but with an audio guide that wasn’t totally functioning we didn’t wander to every corner. After pondering at the incredible investment surely needed to fund such an intricate palace so many years ago, we headed back toward the bustle of Beijing.

The Tiananmen Square (天安门广场) will likely always carry a bit of infamous connotation in protests located there on June 4, 1989, but the afternoon we had a look at the Monument to the People’s Heroes (人民英雄纪念碑, or Renming Yingxiong Jinianbei as pinyin) the square was quite empty; a sole police officer and dozens of cameras I’m sure kept a close watch.

That night, after a dinner at Quanjude for roast duck, we headed up to the Bird’s Nest area to see the facility at night. Its square, too, was desolated, with just a few teenagers riding skateboards and families doing their nightly walk. The Bird’s Nest itself — official name National Stadium, or 国家体育场 — wasn’t lit as spectacularly as I had hoped, but without a tripod the quest wasn’t bound to be anything enlightening (pun intended).

The Olympic torch sculpture, for which I saw and know of no translation, was, however, lit, and brightly enough at that to make pushing the shadows of the willow trees next to it and Olympic Park Observation Tower (奥林匹克公园瞭望塔) behind it difficult.

By the time we circled around to the “front” of the Stadium, the lights of the National Aquatics Center were also turned off, leaving its walls glowing from the screens of nearby buildings. Maybe another time I’ll head back with a tripod and a better idea from where to take the pictures.

About the only lights that weren’t turned off by the time we left were motorists’ headlights; at even 11 PM the 4th Ring Road was still very full in one direction. I can’t imagine driving in this sort of traffic daily; nor can I imagine how quickly a city has to grow to produce this sort of traffic. Even Charleston, which is among the faster-growing areas in the US, is only at one “ring road” after nearly three decades!

The last evening we were in Beijing, we attended the Chaoyang Theatre Beijing Acrobatic Show, which officially doesn’t allow photography. It’s a gripping session, with spectacular stunts and feats of strength and flexibility not usually displayed in occidental performances. Perhaps circuses come close in certain acts but not during the entire show (at least not that I know of; I haven’t attended many circuses). Frankly, I’m not sure how the liability works for the performers. Case in point: the finale of the show is a motorcycle riding act in which seven — I think; it could be nine — riders successively ride around an enclosed metal sphere; the first rider is driving in dizzying circles for perhaps ten minutes before he is let out. The show is admittedly touristy but the feats are no joke and worth the ticket price.

Not far from the Chaoyang Theatre is the CCTV (China Central Television, not closed-circuit television) building. Its architecture is a bit unconventional for China, especially for a city so esteemed as the capital of the country, and has earned the tongue-in-cheek nickname “Big Underwear” from Beijing’s citizens.

It was not unfitting that this be among the last impressions I had of China before boarding another A340-600 back to Munich the next day: it symbolizes a distaste of how the government wanted to portray Beijing as a modern city against its varied heritage, a theme I wrote about last year. But the conflict lies not only with the government’s choice to use modern architecture in place of traditional: how Chinese interpret wealth is arguably the underlying theme. Day after day, situation after situation, I ran into cases where self-entitlement was on full, unchecked, and shameless display, more so this year than any trip in the past. The concept of lining up (British English: queuing) was more and more foreign, to the point where one woman told me flat-out that “lines [queues] aren’t needed here,” and the idea of lending a hand to someone in need was based on whether the courtesy action would improve the lender’s image rather than actual need of help. The country has turned to tourism to fuel random projects without consideration that unmitigated tourism is ruining the ability to have a relaxed vacation and exacerbating the idea outside its borders that the Chinese appear rude, narcissistic, and goal-oriented to a fault, and distressingly more egregiously, that tourism is likely not a long-term solution to bring the deeply impoverished regions into the astonishingly-quickly strengthening “middle” class in the first place.

My reflections on China in the past two years I visited were that it was in a state of organized or structured chaos. Yanking the majority of its population from rags to riches certainly buoyed the country as a whole (and is no small feat) but at the same time gave certain areas a feeling of haphazard neglect. Last year, I cautioned that it would not be unwise to consider the prospects of the future while pondering lessons learned in the past. This year, I was startled and unsettled to see that rather than pick up the best characteristics of other societies or of its own ancient civilizations, China has continued to ignore what made it a successful competitor but has rather embraced ruthlessness and greed, with money practically the sole determinant of whether something could be undertaken or how quickly it could be accomplished. In turn, the whole population seemed more impatient, unwilling to help, and standoffish to impediments to their own gluttony. This is merely annoying when seen in the public; it is devastating when seen within one’s family.

Some of my astonishment can undoubtedly be attributed to my not living in the country. Needing to survive in the wilderness forces behaviors and enforces mentalities previously unthinkable. But judging from my last four trips there, each return I recognize less of the country I came from, a realization that leaves a terrible, empty, gnawing uneasiness inside me. Yet the only way to overcome it is to go back. But in doing so I think I’d just become more numb to it, not do anything to fix it. I’m not quite sure if, then, that acclimatization process is learning cultural tolerance or intolerance; at this point it seems simply bitter.